Plant Pathologist and Mentor

for Sydney Everhart, they go together

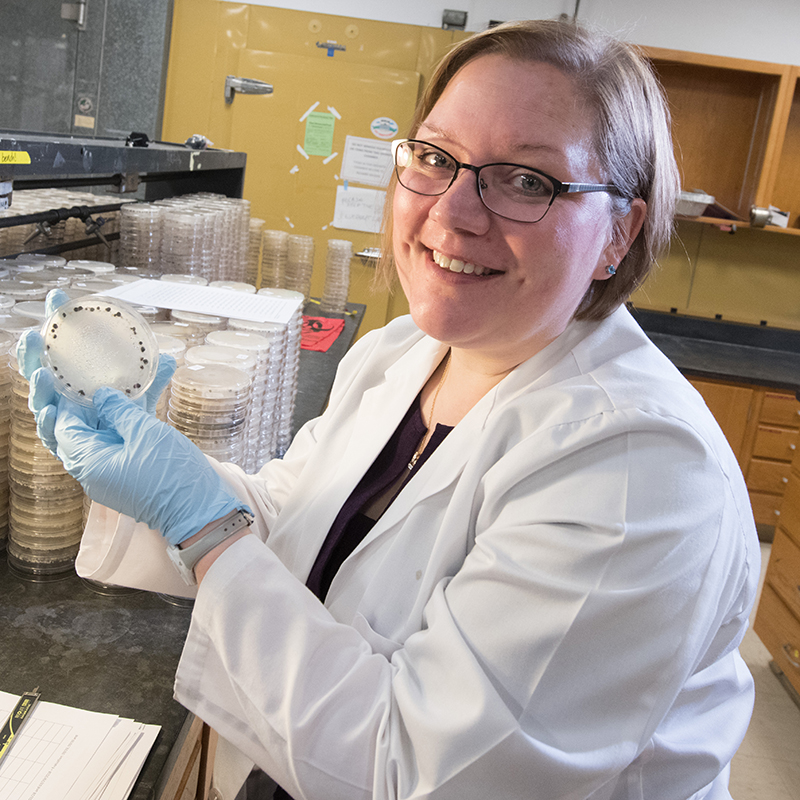

Sydney Everhart is known as a quantitative ecologist to some; to others, a plant disease epidemiologist. And to many more, she is known as a role model and mentor.

Everhart is an assistant professor in the Department of Plant Pathology at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. She studies diseases and disorders of plants, how they occur and what management practices can be used to stop them.

“If we understand where these organisms occur and what factors contribute to these epidemics, we can refine our management approaches to target the disease,” Everhart said.

ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE

Plant diseases are caused by microbial plant pathogens, she explained. A microbial plant pathogen is a disease-causing agent, such as an organism, fungus or bacteria, that is detrimental to the plant host, limiting yield potential or leading to plant death. Everhart has researched many pathogens and diseases, but when she came to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, she decided to target organisms that are important to Nebraska’s economy, such as Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, a fungus that causes white mold disease in soybean. In her lab, Everhart uses advanced molecular tools to better understand the way a disease works and how it is spread. One of these tools is genetic fingerprinting.

“We use the same types of markers in this plant pathogen that are used in human forensics,” she said, explaining that a genetic analysis is done to determine the individual pathogen’s genetic code. “This type of genetic profiling helps us figure out if Farmer A’s pathogen is more closely related to Farmer B’s pathogen or Farmer C’s pathogen, which might indicate there was some type of spread between one or the other,” she said.

In the future, Everhart also hopes to study diseases that affect other crops, such as the frosty pod rot that threatens the cacao plant, from which chocolate is made. Frosty pod rot disease, scientifically known as Moniliophthora roreri, can reduce cacao production by up to 80 percent, Everhart said. By collaborating with researchers from other countries, Everhart hopes to help find solutions for plant diseases that threaten crops around the world.

Plant pathologists also determine the most efficient and economical ways of eliminating plant diseases.

Sometimes, the solutions seem drastic, Everhart said. She shared an example of the Citrus Canker disease outbreak that occurred in citrus trees in Florida about 15 years ago. The trees are important economic drivers, contributing to Florida’s standing as one of the top two orange-producing states in the United States. They also can be grown in backyards by homeowners, Everhart said. Florida instituted an eradication program and then began removing trees from both orchards and homeowners’ backyards to stop the disease-causing organism from spreading to even more fruit trees.

The Florida homeowners were unhappy and sued the state; the result was that the homeowners won the lawsuit.

“The public did not have a good understanding of how important this management decision was and that it could have saved the citrus industry,” Everhart said. “This is a case where educating the public on these plant diseases is extremely important.”

SCIENCE LITERACY

Understanding what the public needs to know and how they need to receive it can make a difference. So can adopting new communication technologies, Everhart said; she has a personal website and social media platforms like Twitter, which she uses to discuss scientific research and understanding.

“We absolutely need to invest in this,” she said.

MENTORING

Even when she was young, Everhart had an interest in plants, partly because of her father. “He was my mentor throughout my career. He was a community college teacher who taught horticulture and plant identification, and later became an Extension horticulture field specialist. We would spend a lot of the time in the woods looking for morel mushrooms, but also identifying things. He played a central role in getting me to where I am today as a scientist.”

In an effort to provide others with positive relationships, Everhart was a founding leader in the Cultivate ACCESS program, or Cultivate Agriculture Career Communities to Empower Students in STEM. Cultivate ACCESS was started at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln and is funded by the United States Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture (USDA-NIFA). It focuses on pairing mentors from underrepresented groups with high school students who can relate to their mentor in that aspect.

“These mentors are people who appear like them. So, they may be women or maybe another underrepresented group from the agricultural science careers,” Everhart explained. “Scientific studies have shown that this increases participation and that people may not think of going into plant pathology or other ag fields because they don’t see people who look like them in those fields.”

According to Everhart, a real positive, driving force in students’ lives comes from having someone who supports their career goals, whether this is a mentor or a parent. Even though Everhart may not be involved in the mentoring aspect of Cultivate ACCESS, she is a mentor for several graduate students and undergraduates who are working in her lab or taking her classes. In this way, Everhart has turned her father’s mentorship into a personal goal of training the next generation of scientists, saying, “There’s no way I could ever repay the lifetime of mentorship that my father provided me, so my only option is to pay it forward.”